The

XJR-14’s monocoque didn't have the usual piercings in the structure for

doors. Through a clever rules interpretation, though following on

the Peugeot 905’s coattails, the side windows were hinged and

subsequently this is how the driver entered and exited the car,

allowing for a much stiffer monocoque.

The

XJR-14’s monocoque didn't have the usual piercings in the structure for

doors. Through a clever rules interpretation, though following on

the Peugeot 905’s coattails, the side windows were hinged and

subsequently this is how the driver entered and exited the car,

allowing for a much stiffer monocoque. Laminated inner and outer skins of carbon fiber twill with aluminum honeycomb in between, in addition to loads of unidirectional carbon fiber, the XJR-14’s tub was laid up in female molds and in two pieces, a top and a bottom. The tub halves were then glued together but not before carbon bulkheads were inserted.

The completed tub weighed around 100 lbs (45-47 kgs) and in house torsion testing showed approximately 80,000 lbs per degree of torsional rigidity.

The XJR-14's roll over hoop was steel and bolted to hard points located at the corners of the cockpit opening.

The

Jaguar's short front overhang meant the main crash box was

shorter than desired and subsequently the XJR-14 struggled a bit to

pass FISA's crash test. But FISA's regulations, which weren't

even particularly stringent, simply

required

that there not be any damage aft

of the pedal face. And while crash testing of the XJR-14

revealed

a crack in the tub floor that propagated past the pedal face, the

solution was relatively simple, says Steve Farrell, race engineer for

TWR (1989-1992), "The car didn't do as well as we had hoped in the

crash testing, but in the end the FIA allowed us to 'draw a line' at

the point where damage finished in the test and for us to agree that we

would always set the pedals behind this line."

The

Jaguar's short front overhang meant the main crash box was

shorter than desired and subsequently the XJR-14 struggled a bit to

pass FISA's crash test. But FISA's regulations, which weren't

even particularly stringent, simply

required

that there not be any damage aft

of the pedal face. And while crash testing of the XJR-14

revealed

a crack in the tub floor that propagated past the pedal face, the

solution was relatively simple, says Steve Farrell, race engineer for

TWR (1989-1992), "The car didn't do as well as we had hoped in the

crash testing, but in the end the FIA allowed us to 'draw a line' at

the point where damage finished in the test and for us to agree that we

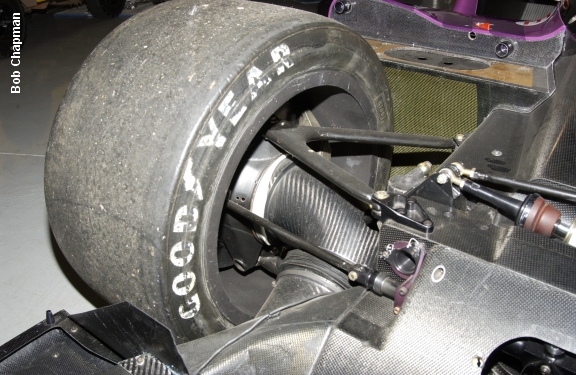

would always set the pedals behind this line." The

torsion bar suspension allows for a more compact package at the front

of the car. The rocker arm rotates on the

longitudinally

mounted torsion bar. The torsion bar itself is hidden by the

monocoque though is accessible from the front (1). The

torsion bar rotated when the pushrod moved and was connected to the pushrod via a bellcrank (2). The bar’s

resistance

to movement was determined by its diameter, wall thickness,

and

length

and thus was the equivalent spring rate.

The

torsion bar suspension allows for a more compact package at the front

of the car. The rocker arm rotates on the

longitudinally

mounted torsion bar. The torsion bar itself is hidden by the

monocoque though is accessible from the front (1). The

torsion bar rotated when the pushrod moved and was connected to the pushrod via a bellcrank (2). The bar’s

resistance

to movement was determined by its diameter, wall thickness,

and

length

and thus was the equivalent spring rate.The dampers (3) are mounted horizontally on the top of the tub, transversely across the chassis. The anti roll system (4) picks up off the bellcrank through a pushrod.

“As far as I know it was unique at that time,” says TWR Chief Designer John Piper regarding the XJR-14's torsion bar front suspension. Ultimately packaging drove the choice of the torsion bars, “it made the pushrod angle better whilst keeping the front nose height low.” This was always important in keeping frontal area to a minimum. Ride height could be altered with just a few turns of a single, centrally mounted, screw jack, and swapping out different stiffness torsion bars could be done “in seconds” making the whole system ultimately more user friendly.

If you look carefully in the image, at upper right, where the bellcrank mounts to the tub, you can see the repaired section of #591's tub caused by the 1992 accident at Lime Rock.

The

XJR-14's brake inlets were incorporated into the structural outriggers,

the outriggers being hollow and open on the inlet end. They

bolted to the sides of the crash box. And while not part of the

crash structure per se, says John Piper, "I think Ross had hoped they

might contribute some energy dissipation, but in the end they didn’t

much."

The

XJR-14's brake inlets were incorporated into the structural outriggers,

the outriggers being hollow and open on the inlet end. They

bolted to the sides of the crash box. And while not part of the

crash structure per se, says John Piper, "I think Ross had hoped they

might contribute some energy dissipation, but in the end they didn’t

much."The headlights seem almost as an afterthought, certainly for an endurance racer. Though in its life time, the XJR-14 never contested either a 24 or 12 hour race.

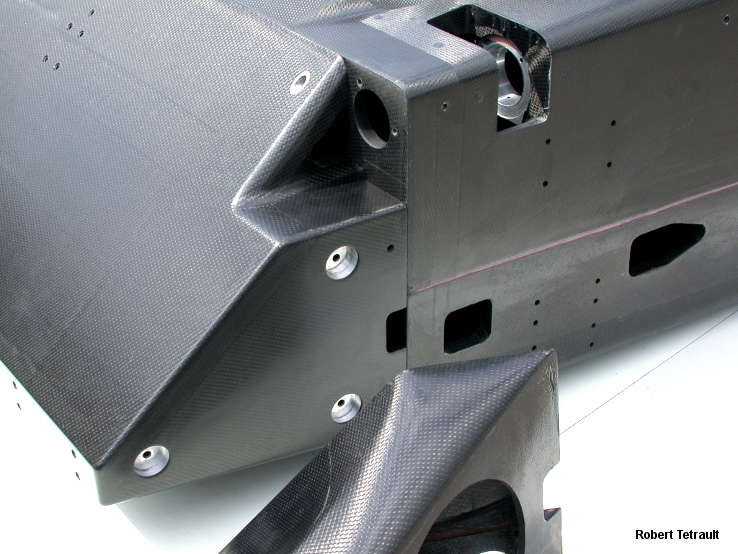

The

outriggers bolted to the side of the primary crash structure. The

round hole in the outboard face of the outrigger (just visible) is where the brake

ducting that fed directly to the upright passed out of the outrigger.

The

outriggers bolted to the side of the primary crash structure. The

round hole in the outboard face of the outrigger (just visible) is where the brake

ducting that fed directly to the upright passed out of the outrigger.You can also see here the very short impact structure.

The

XJR-14's front brake ducting was especially

elegant. "Brake

ducting was always an afterthought on most sports cars with horrible

bits of convoluted hose that only stayed intact for a few laps." says Piper. The traditional

method of using flexible wire

hosing as brake ducting had the drawback of being susceptible to being

dislodged during the race as it was typically attached via hose clamps

and

little else.

The

XJR-14's front brake ducting was especially

elegant. "Brake

ducting was always an afterthought on most sports cars with horrible

bits of convoluted hose that only stayed intact for a few laps." says Piper. The traditional

method of using flexible wire

hosing as brake ducting had the drawback of being susceptible to being

dislodged during the race as it was typically attached via hose clamps

and

little else.

Rigid

brake ducts fed into the

upright/brake calipers but pivoted on elbow joints (white), each

machined from a billet

of Teflon, allowing for steering input.

To allow for flex within the system bellows attached

the elbow to the

primary feed. The

bellows were held in

place by a spring. The

front pushrod

pierced the brake duct though was sealed by rubber skirts on either end.

Rigid

brake ducts fed into the

upright/brake calipers but pivoted on elbow joints (white), each

machined from a billet

of Teflon, allowing for steering input.

To allow for flex within the system bellows attached

the elbow to the

primary feed. The

bellows were held in

place by a spring. The

front pushrod

pierced the brake duct though was sealed by rubber skirts on either end. Packaging

at the front was so tight, given the need to accommodate the front wing,

as well as the crash structure, that the brake and clutch fluid

reservoirs

were moved to the front of the side pod, being accessible through a

hatch after the nose was removed.

Packaging

at the front was so tight, given the need to accommodate the front wing,

as well as the crash structure, that the brake and clutch fluid

reservoirs

were moved to the front of the side pod, being accessible through a

hatch after the nose was removed.