The

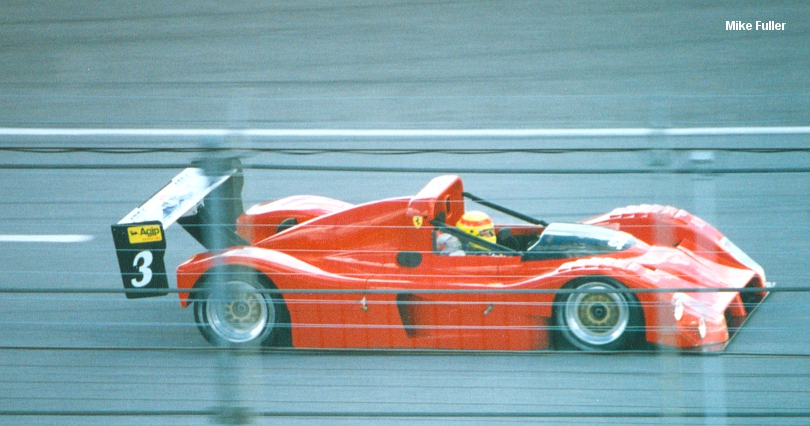

333 was first displayed to the public at Sebring in 1994. Some of

the design details would change based upon IMSA's approval of the type.

The car's original air management had the inside face of the front wheel

well open with low pressure air escaping via that route in conjunction

with air flow from the diffuser. IMSA made Ferrari close that opening

up and also mandated the bodywork around the front wheel fully cover the

circumference above the axle centerline.

The

333 was first displayed to the public at Sebring in 1994. Some of

the design details would change based upon IMSA's approval of the type.

The car's original air management had the inside face of the front wheel

well open with low pressure air escaping via that route in conjunction

with air flow from the diffuser. IMSA made Ferrari close that opening

up and also mandated the bodywork around the front wheel fully cover the

circumference above the axle centerline. The

definitive 1994 Ferrari 333 SP with short nose and convex nose shape, upright sidepod oil cooler duct.

The

definitive 1994 Ferrari 333 SP with short nose and convex nose shape, upright sidepod oil cooler duct. The

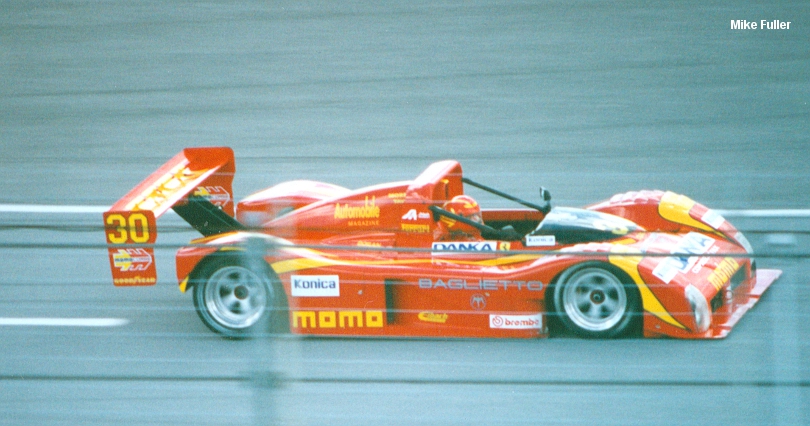

1995 car differed in many aspects. Namely the longer nose and

concave

top shape as well as the modified cooler intake in the sidepod

flank.

The rear wing was also moved forward compared to the '94 variant

resulting

in a forward shift in the center of pressure which in turn helped

reduce

aerodynamic understeer. It's also interesting that the entire

rear wing assembly has as slight nose high attitude, angling the

endplate forward at the bottom (closing the gap between the endplate

and the trailing edge of the rear bodywork). This would have the

effect of reducing drag and relevant to a Daytona-specific setup.

The

1995 car differed in many aspects. Namely the longer nose and

concave

top shape as well as the modified cooler intake in the sidepod

flank.

The rear wing was also moved forward compared to the '94 variant

resulting

in a forward shift in the center of pressure which in turn helped

reduce

aerodynamic understeer. It's also interesting that the entire

rear wing assembly has as slight nose high attitude, angling the

endplate forward at the bottom (closing the gap between the endplate

and the trailing edge of the rear bodywork). This would have the

effect of reducing drag and relevant to a Daytona-specific setup. By

2000 the 333 SP was showing it's age. With a chassis design that traced

its origins to 1993 it was no mean feat that it was competitive all those

years. But changing engine regulations began to have it's toll.

When the 333 SP was introduced in '94 under the IMSA WSC regulations, the

engine (as all competitors) ran with unfettered engine inlets. But soon

thereafter world sportscar racing sanctioning bodies (IMSA, FIASCC, USRRC

and follow on Grand-Am Series, ALMS, ACO, and Le Mans) began to implement

engine inlet restrictors under the guise of reducing power, costs, and

speeds. But by this point the 333 SP wasn't particularly well supported

by the factory. And therefore the Ferrari teams began to suffer a

disproportionate loss in power given the lack of restrictor engine development

in the face of the new engine restrictor regulations. And while some

of the sanctioning bodies began to note the slide (the FIASCC series gave

the 5-valve Ferrari engines a .5 mm increase in inlet restrictor in order

to shore up the Ferrari runners), such help wasn't forthcoming in the U.S.

By

2000 the 333 SP was showing it's age. With a chassis design that traced

its origins to 1993 it was no mean feat that it was competitive all those

years. But changing engine regulations began to have it's toll.

When the 333 SP was introduced in '94 under the IMSA WSC regulations, the

engine (as all competitors) ran with unfettered engine inlets. But soon

thereafter world sportscar racing sanctioning bodies (IMSA, FIASCC, USRRC

and follow on Grand-Am Series, ALMS, ACO, and Le Mans) began to implement

engine inlet restrictors under the guise of reducing power, costs, and

speeds. But by this point the 333 SP wasn't particularly well supported

by the factory. And therefore the Ferrari teams began to suffer a

disproportionate loss in power given the lack of restrictor engine development

in the face of the new engine restrictor regulations. And while some

of the sanctioning bodies began to note the slide (the FIASCC series gave

the 5-valve Ferrari engines a .5 mm increase in inlet restrictor in order

to shore up the Ferrari runners), such help wasn't forthcoming in the U.S.

For the 2000 season, Kevin Doran of Doran Racing replaced the 4.0 liter Ferrari V12 engine with a 4.0 liter Judd GV4 V10. According to Kevin Doran the swap was a no brainer, "The Judd was lighter, more powerful, (had) better fuel economy and (was) cheaper than the Ferrari, need there be more?" And the combination brought renewed fight into the aging Ferrari chassis. The chassis engine combination would go on to win two Grand-Am events in 2001 (Watkins Glen and Road America).

While seemingly a straight forward engine swap, the Judd needed spacer plates added front and rear as it was shorter than the Ferrari V12. "It was a big project, very few teams could complete. We did it though, without modifying the tub or the gearbox," says Doran. The plates had both the Judd and Ferrari bolt patterns and attached to the Judd motor and then picked up off the Ferrari mounts on the back of the monocoque and the front of the bellhousing.

Ultimately the writing was on the wall for the 333 SP. That few other 333 SP teams opted to make the engine swap is understandable given the needed design engineer resources and experience coupled with the fact that new chassis were appearing that were substantially quicker than the Ferrari (Doran would switch to a Judd GV4 V10 powered Crawford chassis in '01 though would revert back to tried and true Ferrari Judd 025, then to a Judd V10 powered Dallara in '02 [winnig Daytona that year]).